Throughout the history of the human race, there have always been individuals who stood out from the rest of mankind. These people were more often than not, pioneers, adventurers, men and women who were seemingly ahead of their time. These people led the way towards the advancement of the society as a whole. Some used the influence they gained to relentlessly pursue whatever they first became famous for, while others used their influence to sway the minds of the public in other matters. There were those who bathed in the spotlight as well as those who hid from it. But one thing can be sure of, these people definitely left a lasting mark in history. One such person was Charles Lindbergh.

Throughout the history of the human race, there have always been individuals who stood out from the rest of mankind. These people were more often than not, pioneers, adventurers, men and women who were seemingly ahead of their time. These people led the way towards the advancement of the society as a whole. Some used the influence they gained to relentlessly pursue whatever they first became famous for, while others used their influence to sway the minds of the public in other matters. There were those who bathed in the spotlight as well as those who hid from it. But one thing can be sure of, these people definitely left a lasting mark in history. One such person was Charles Lindbergh.

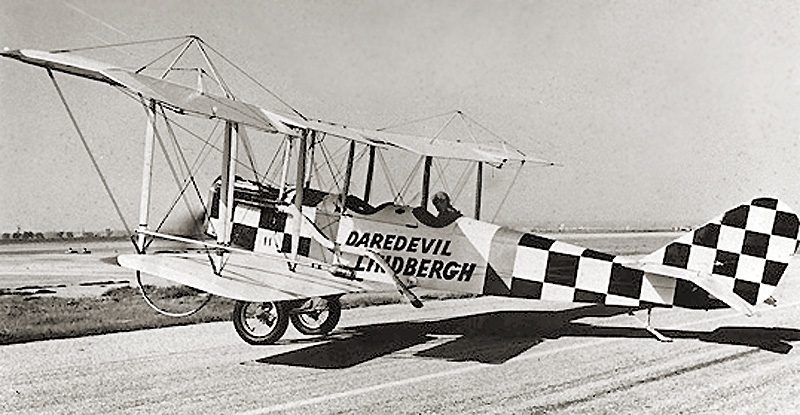

Hailing from the United States of America’s Michigan state and specifically Detroit city, Charles Augustus Lindbergh was born on February 4, 1902. The future aviation icon was raised by a mother who was a lawyer and a father who was a congressman, on a farm in Minnesota. He first took up Mechanical Engineering at the University of Wisconsin, which he eventually left to pursue his curiosity in flying. By 1923, he had gone to Lincoln, Nebraska where he successfully completed his first solo flight. After which, he spent his time exhibiting and honing his flying skills as a daredevil pilot during local fairs and other such events. In 1923, he joined the United States army and trained as an Army Air Service Reserve. Later on, he served as an airmail pilot, traveling between Chicago and St. Louis.

Around this time, which was the early 1920’s, a hotel owner by the name of Raymond Orteig had announced a price offer of $25,000 to the first person to successfully pilot a plane none stop and alone from New York, U.S.A. to Paris, France. Quite a few people had already attempted this feat and failed before Lindbergh came into the scene. He solicited support from some businessmen located in St. Louis. Before long, he set forth from Long Island’s Roosevelt Field on May 20, 1927, while piloting his soon-to- be iconic plane named Spirit of St. Louis.

Flying across the Atlantic Ocean by himself nonstop for 33.5 hours over a span of 3,600 miles, Lindbergh arrived at France’s Le Bourget Field, which was located close to the city of Paris. His arrival was met with more than a hundred thousand local spectators who had come to witness aviation history in the making. His successful solo transatlantic flight made him into an instant celebrity causing people to crowd around him wherever he went. It also earned him countless prestigious honors such as the Distinguished Flying Cross medal from Calving Coolidge who was then the US president.

With his new found fame, Lindbergh spent much of his time in promoting the aviation field while going around the United States with his iconic plane, the Spirit of St. Louis. While visiting various cities in the US, he would participate in countless parades as well as give speeches. His fame grew to such height that he was soon regarded as an international celebrity who was nicknamed “Lucky Lindy” and “The Lone Eagle”. By 1927 he released a book titled “We” about his historic flight, which quickly became a bestseller. Throughout all his rising fame and influence, Lindbergh had always stuck to helping the aviation industry as well as other causes which he felt important.

On another such instance, Charles Lindbergh had completed a goodwill trip from the US to Mexico, where he met the US Ambassador’s daughter, Anne Morrow. A few months later in 1929 Lindbergh had married Morrow, whom he would teach how to fly airplanes. The two would cherish the privacy of flying together, with Morrow acting as Lindbergh’s co-pilot. The husband and wife would travel far and wide, their routes eventually becoming the basis of commercial air travel around the world.

After years in the spotlight, Lindbergh and his wife decided to find a bit of calm away from all of the attention. They retreated to a quiet estate in Hopewell, New Jersey, where they hoped to start their own family. Soon after, the arrival of a beautiful baby boy who entered their lives made their hopes come true. They named the new addition to their family, Charles Augustus, Jr. Everything was seemingly well for the Lindbergh family, but when young Charles was just 20 months old, a tragedy struck. An intruder had used a homemade ladder to scale up the second story of their home, taking their son away. The world was shocked to learn about the crime when headlines started reporting on the incident. In order to facilitate the return of his son, Lindbergh chose to pay a ransom worth $50,000 but it was all for naught. A few weeks after the ransom was paid, the body of their dead son was found in the woods near their estate. By tracing the marked bills used for the ransom, the police were led to Bruno Hauptmann who was tried, found guilty of the crime and executed in 1936.

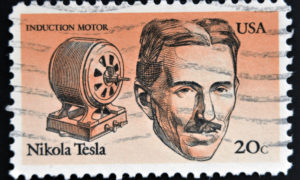

With the constant media frenzy caused by the tragedy involving their son’s death, the Lindbergh’s chose to retreat to Europe to escape the unwanted attention once more. There, Lindbergh dabbled in scientific research and with the help of a French surgeon, was able to invent an early form of an artificial heart. Lindbergh continued being a special adviser for Pan-American World Airways while staying in Europe and at one point was actually invited to view the German Aviation facilities which he found impressive.

At the onset of World War Two, Lindbergh was of the opinion that the German air force could not be defeated. Thus, he tangled with the America First Organization and supported the idea of the United States, keeping a neutral stance on the war that was engulfing Europe. But with the catastrophe that was Pearl Harbor, his mind changed and he began to actively support the war by joining hands with Henry Ford in the creation of Bomber Planes as well as testing new aircraft being built by the allies. Towards the end of his life, Lindbergh retired to a remote home on the island of Maui, Hawaii. On August 26, 1974, Charles Lindbergh died of cancer.